Dennis Banks (Nowa-Cumig), born on April 12, 1937, and passing away on October 29, 2017, was a prominent Ojibwe activist and co-founder of the American Indian Movement (AIM). His tireless dedication to Native American rights and his leadership in high-profile protests brought crucial attention to the historical injustices faced by Indigenous peoples in the United States. Banks’s life story is one of resilience, activism, and a deep commitment to advocating for his people.

Early Life and the Impact of Boarding Schools

Dennis Banks, a key figure in the American Indian Movement, photographed in 1974.

Born on the Leech Lake Reservation in northern Minnesota, Dennis Banks, or Nowa-Cumig meaning “in the center” in Ojibwe, belonged to the Turtle Clan. His early years were marked by poverty, and at the young age of five, he was forcibly removed from his grandparents’ care and placed in the U.S. government’s Native American boarding school system. These institutions, designed to assimilate Indigenous children into white American culture, often had a devastating impact, stripping children of their languages, cultures, and family connections. Banks experienced this firsthand, attending multiple boarding schools and frequently running away, a testament to his resistance against forced assimilation. At 17, he permanently left the boarding school system, returning to Leech Lake.

Unable to find stable employment, Banks enlisted in the U.S. Air Force. His time in the military included a period stationed in Japan, where he married and subsequently went absent without leave. This led to his arrest and return to the United States. Following his discharge, Banks relocated to Minneapolis, Minnesota. Life in the city presented new challenges, and he struggled to support his family, leading to involvement in petty crime. A turning point came in 1966 when he was convicted of burglary and served approximately two and a half years in prison. This experience, however, would inadvertently set the stage for his future activism.

The Genesis of AIM and the Fight for Native Rights

Upon his release from prison in 1968, Dennis Banks, alongside Clyde Bellecourt, whom he met while incarcerated, and other Native American leaders, established the American Indian Movement (AIM). Initially, AIM focused on addressing the immediate needs of Native Americans in Minneapolis, particularly those struggling with urban adjustment and systemic discrimination. However, the organization’s scope quickly expanded as membership grew and the urgency of broader Native American rights issues became apparent.

Native American activists occupy Alcatraz Island

Native American activists occupy Alcatraz Island

Native American activists participating in the occupation of Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay, November 1969, a pivotal moment in the fight for Indigenous rights.

In 1969, Dennis Banks met Russell Means, and together they became the most recognizable faces and driving forces behind AIM. The movement gained national prominence through a series of bold and impactful protests. One of the earliest and most symbolic was the occupation of Alcatraz Island, beginning in November 1969. Banks and AIM joined the “Indians of All Tribes” in this 18-month occupation, reclaiming the island in the name of Native American people and highlighting broken treaties and the federal government’s failures.

AIM’s activism continued with a powerful Thanksgiving Day protest in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1970. Banks and Means declared Thanksgiving a national day of mourning, a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of European colonization for Native populations. The protest included the symbolic takeover of a replica of the Mayflower, directly confronting the romanticized narrative of American origins.

Trail of Broken Treaties and Wounded Knee: Confronting the Government

In 1972, Dennis Banks played a central role in organizing the Trail of Broken Treaties. This ambitious cross-country caravan brought hundreds of Native activists to Washington, D.C., to demand the U.S. government address long-standing grievances and recognize Native treaty rights. When planned meetings with government officials were abruptly canceled, AIM members responded with a forceful occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) building, holding it for six days and further amplifying their demands on a national stage.

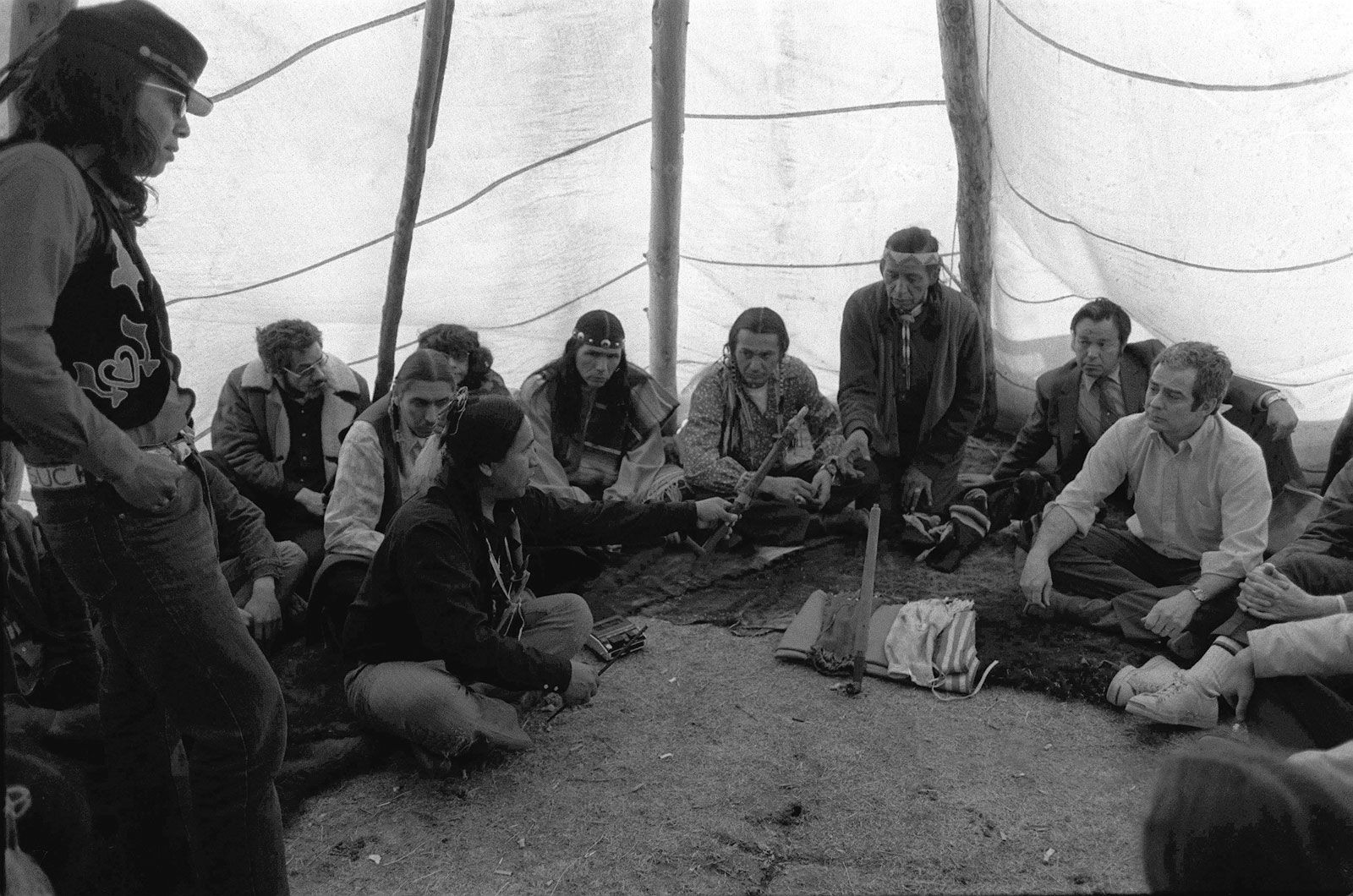

American Indian Movement standoff at Wounded Knee 1973

American Indian Movement standoff at Wounded Knee 1973

Members of the American Indian Movement and U.S. authorities in a tense meeting during the 1973 Wounded Knee standoff in South Dakota.

The following year, in 1973, Banks and Means orchestrated another landmark protest: the Wounded Knee occupation. Approximately 200 AIM members and supporters occupied Wounded Knee, South Dakota, the site of the horrific 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre where hundreds of Lakota Sioux were killed by U.S. troops. This location was deliberately chosen to symbolize the historical trauma and ongoing injustices faced by Native Americans. The protest aimed to expose corruption within the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and to broadly address the continued mistreatment of Indigenous peoples. The federal government responded with a heavy armed presence, leading to a tense 71-day standoff. During the siege, two activists tragically lost their lives, and a federal marshal was seriously wounded. While Banks and Means were arrested and tried for their roles in the Wounded Knee occupation, the case was ultimately dismissed due to prosecutorial misconduct, highlighting the complexities and controversies surrounding the government’s response to AIM.

Legal Battles and Later Life

Even before Wounded Knee, Dennis Banks faced legal challenges. Weeks prior to the occupation, he had been involved in a protest in Custer, South Dakota, sparked by the lenient charges against a white man who killed a Native American man. The protest escalated into a riot, and Banks was charged with rioting and assault, eventually being convicted in 1975.

Facing this conviction, Banks went underground, spending nine years as a fugitive in California and New York. In 1984, he returned to South Dakota, surrendered, and served 14 months in prison. Upon his release, he dedicated himself to community healing, working as a counselor on the Pine Ridge Reservation, assisting individuals struggling with drug and alcohol addiction.

In his later years, Dennis Banks expanded his creative pursuits, venturing into acting. He appeared in notable films such as Thunderheart (1992) and The Last of the Mohicans (1992), the latter reuniting him with Russell Means on screen. Beyond activism and acting, Banks also demonstrated entrepreneurial spirit, founding a company that produced maple syrup and wild rice, promoting traditional Native American foods. His life story and reflections on activism were captured in his memoir, Ojibwa Warrior: Dennis Banks and the Rise of the American Indian Movement, published in 2004, co-written with Richard Erdoes.

Dennis Banks’s legacy is profound. He was a central figure in the fight for Native American rights, using direct action and protest to challenge the U.S. government and raise public awareness. His work with AIM and his unwavering commitment to Indigenous sovereignty continue to inspire activists and shape the ongoing struggle for justice and equality for Native peoples today.